On Complexity…or From Customers to Kubernetes

Call it productive procrastination if you will. Working on a research piece recently, I started contemplating the inherent complexity of customer relationships. It wasn’t always so hard. Once upon a time, customers walked through the door, called, or wrote. Observing them and inferring their priorities and preferences wasn’t too difficult. Neither was talking to them.

Today, customers compare online while they’re in a store. They research whatever they’re about to buy before they ever call a salesperson. They expect transparency, consistency, and easy transactions both in their private lives as consumers and in their professional lives as decision-makers.

Meanwhile, for the companies they do business with, simply keeping track of all the ways customers communicate is a challenge. Email, chat, text, call, social media, in-app messaging—the list goes on. Want to really mess with the system? Try sending a snail-mail letter.

If communication channels alone present this level of complexity, I thought, how are we supposed to get the complicated things right, like personalization? Or using the insights we have about our customers to design great experiences? What about evolving our offerings and business strategy over time?

Managing complexity, it struck me, is the key—not just to getting customer relationships right, but to so many of the big business and technology challenges. Complexity always exists somewhere in the system. As businesses, we have a choice: we can put that complexity on our customers or we can take it on ourselves.

Then I remembered reading something long ago about how to do it well and why so few organizations seem to get it. Something about when keeping it simple was, well…just stupid.

Off to the other room I headed, and down, down, down the rabbit hole I fell…

There among the many treasures of my over-stuffed bookshelf at last I found it: Designing the Global Corporation by Jay R. Galbraith.[1] He wrote about organizational models and management practices in multinational companies, not customer experience per se, but Galbraith squarely focused on understanding the impact of complexity on customers.

Here’s the money quote I’d been looking for on page one (emphasis is mine): “At the heart of the issue is the manager’s difficulty embracing the complexity of the organization and building the capability to manage it. Most managerial mindsets…may also be influenced by the so-called management principle of ‘keeping it simple.’ Yet serious students of cross-border [read: complex] organization have arrived at the position keeping it simple is stupid; the world is complex, and a simple organization in a complex world becomes less and less viable.â€

Galbraith’s main point is that—stay with me here—a company’s organization must be as complex as its business. That is, if your company is doing anything more than selling a single offering to a single type of buyer, you need something more than a very simple organization model. More importantly, you need the management capability to deal with the commensurate complexity. Otherwise, you make it the customer’s job to deal with complexity. And that’s bad for business.

The same principles apply to all kinds of customer relationships and interactions. Complexity exists somewhere in the continuum or value chain. Either we take it on as businesses and, hopefully, manage it effectively or we push it on to customers to manage for themselves. There are certainly cases where customers want and expect to deal with complexity themselves (think flea markets…I’m shuddering as I do). In the vast majority of cases, however, our priority and our vested interest as businesses is to understand and deal with that complexity in order to make things simple for our customers—whether B2B or B2C.

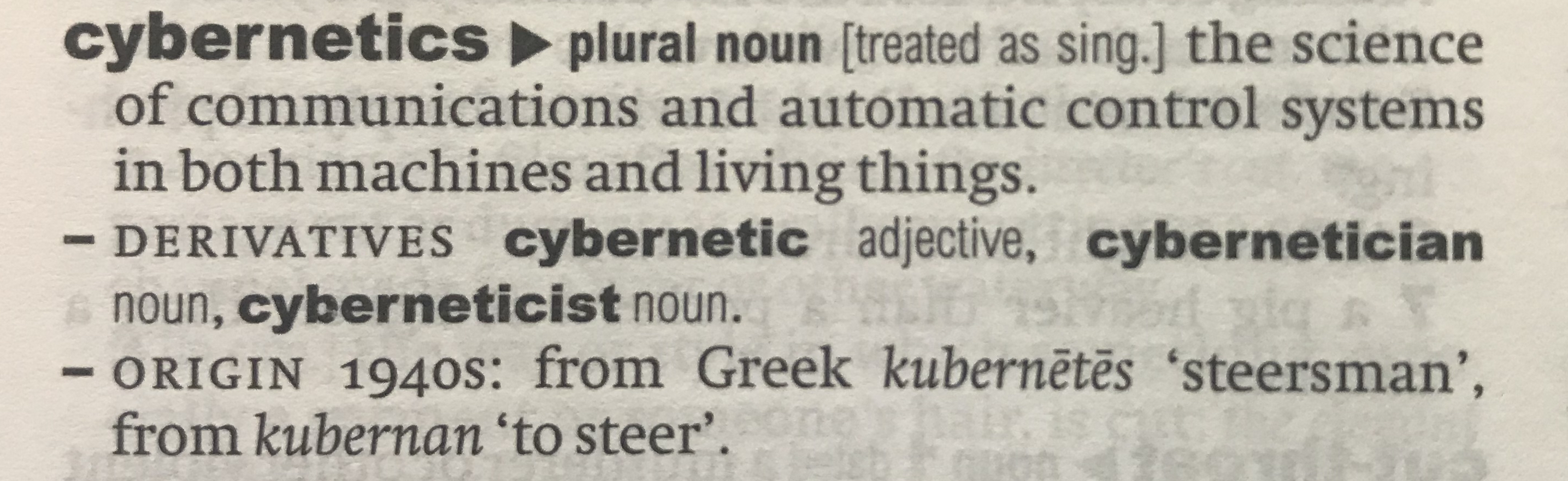

My fall down the rabbit hole continued. Throughout his book, Galbraith references the law of requisite variety or requisite complexity. The former originates in control theory and the latter is the application to organizations. My search for more background on control theory turned up multiple references to general systems theory and cybernetics.

Cybernetics?? My first thought was of L. Ron Hubbard. (Fear not. Scientology has no role in this story. Do like his first initial though.)

Back to my bookshelf and the comforting embrace of the Oxford Dictionary of English.[2] This is where things started to come full circle:

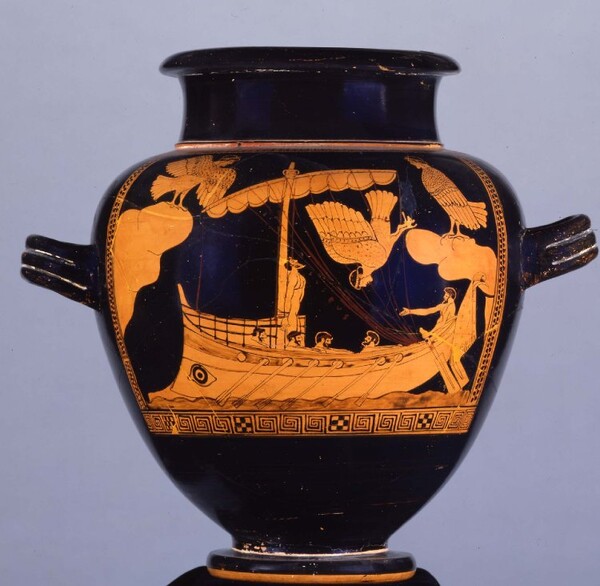

Here we are, back at the original challenge: how to use technology effectively to facilitate (dare I say simplify) communication and interactions between people. And increasingly, how to use technology tools to automate the things we want to make easy and fast.

As I emerged from the rabbit hole, this revelation blew my mind a little bit. I honestly hadn’t even thought about the name Kubernetes much before that moment.

We are at a unique and important moment in time when it comes to the intersection of business and technology. Technology has created many of our challenges; it also provides an indispensable means of addressing them.

Whether consolidating communication channels or containerizing workloads, we must as businesses keep finding better ways of using technology to help us manage complexity. That means, among other things, using technology tools to move up levels of abstraction so that we’re concentrating less on how the technology works and more on what we’re trying to do with it.

This is where we are—taking very old ideas (the steersman) and using new technologies (containers, chatbots, AI-driven analytics…you name it) to apply them in wholly different contexts. Today, we’re steering through the complexities of customer relationships that span digital and old-school modes.

To succeed, we must use these new capabilities to refocus on the some very old fundamentals—like understanding our customers—and get them right.

[1] Galbraith, Jay R. (2000). Designing the Global Corporation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc., A Wiley Company.

[2] Apologies to Merriam-Webster. I was living in England when I bought it.

Header image credit: The Siren Vase courtesy of the British Museum