I'd like to share some interesting lessons learned from an exercise in improving collaboration conducted recently in a large public-sector organization. While this précis is not short, it really just scratches the surface, so contact me if you want to chat about it in more detail - I'd be happy to share.

The order came from the top - find out why we're not collaborating enough and fix it! True, people were working in isolation much of the time, hiding work from others, re-inventing the wheel continuously, especially when possession of that work's outcome (a) gave them power over co-workers and/or (b) gave them value in the eyes of seniors. But in general the nature of the work lent itself well to collaboration, and most people really wanted a better quality of interaction with colleagues. And yet, despite efforts to fix the situation, such as the development of thematic portals, and the installation of IM and video chat facilities, really effective collaboration remained low. What we found out was this:

1. To improve collaboration, define it in a way that brings value to your organization, and aim for that definition.

"Collaboration" in the abstract is just too nebulous to go out and "improve" on. In our context we defined it as actions of cooperation between colleagues that improve outcomes, provide learning experiences, and institutionalize knowledge. In other words, working together (a) produces deliverables that are better than if done alone (greater than the sum of their parts), (b) allows information and techniques to be transferred from one person to another, and (c) through that transfer allows knowledge to permeate into the fabric of the organization - its people and its products. Of course we know that committees can produce outcomes that are poor compromises, so it's not just about getting in a room together - its about collectively aspiring to better quality through a sense of common purpose. And please note that purpose is a key word here - collaboration efforts need to be centred around a real business purpose or they won't take hold.

2. Collaboration must be built on a solid infrastructure

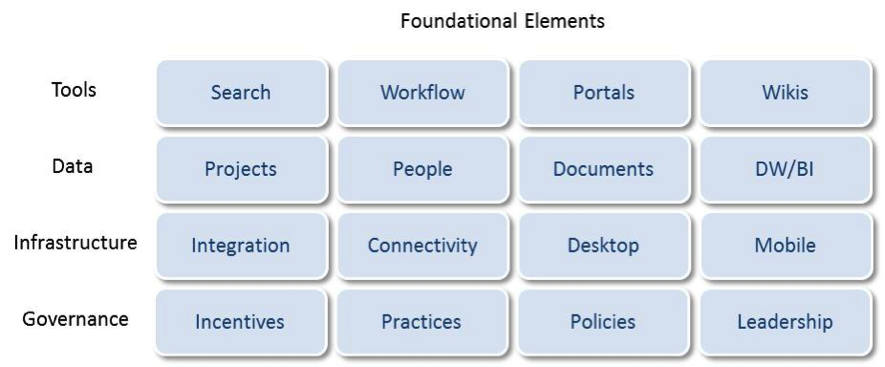

What is this infrastructure? We divided it up into four layers of "foundational elements":

Starting bottom left and working up:

Incentives: Be careful how your organization* is incentivized - too many large organizations have periodic evaluation frameworks which favour individualism, while smaller companies are ad-hoc. Group collaboration must be part of any incentive/reward structure.

Practices and Policies: Practices are the informal but engrained ways of doing things that make their way into the way we work, until we think they are actual rules. Once entrenched, they're difficult to break away from, but any working practices that favour individualism need to be identified and changed. Policies are the actual written rules, and also need to be identified and changed.

Leadership: The biggest success factor of all. The senior most people in the organization need to demonstrate collaboration and require it of their reports, ensuring permeation through the ranks. Interestingly, the leadership isn’t all senior: natural leadership at all levels needs to be nurtured too. Some call them "Champions", but either way, find the individuals that will run with a new concept and pull others along with them, and make sure they get your full support – and get rewarded.

Integration: Organizations structured in silos will always work that way, and information systems that are disparate and support the silos with little to no inter-connectivity will exacerbate the problem. Collaboration thrives in environments that are integrated both structurally and informatically. Yes, that’s now a word!

Connectivity: Global organizations need the tools and telecoms bandwidth to communicate fast and effectively. If it's hard to speak or IM with someone far away, or even ten cubicles away, people will tend to try and solve problems alone.

Desktop and Mobile: All elements, including hardware, desktop programs and mobile apps need to be of quality and performance comparable to that which employees now enjoy in their personal lives. Hoping that people will connect and collaborate with the aid of a lousy phone or tablet app is a dream, not a hope. The quality of experience out there is too great now for anything less than excellent to take hold.

The Data Layer: Whatever your business, the information supporting it needs to be of high quality and highly available. Information about financial and material resources, about projects (the things we're working on) and about people (the skills and other characteristics of our staff) are primordial to generating collaborative links that would not otherwise have occurred. For example, "Oh, I know a guy in sales who can do that..." just isn't enough any more. We need to consult our internal skills base and find the best person, anywhere in the company, whether for a quick piece of advice or longer-term assignment.

The Tools Layer: As soon as we say “tools” everyone thinks about an enterprise-social tool like Yammer or any one of its 100-or-so (literally) competitors. We'll come back to that shortly but for the time being the tools infrastructure elements we're talking about include: a mature portal structure, a comprehensive enterprise search facility, and the established use of (what should be) core technologies in your business such as workflow engines and wikis. Plonking in a "Facebook for companies" without being able to search your own company's information with an engine at least as effective as Google is not going to support your definition of collaborative value.

Bottom line: Any fundamental weakness in any of the foundational elements will critically hamper collaboration.

3. The Three Biggest Issues

Once we'd figured out our foundation model and experienced its relevance, we realized that there were a couple of other pieces to the puzzle that merit separate mention:

A. The biggest enemy: EMAIL. Email is the quintessential necessary evil. While we can no longer live without it, it's also one of the biggest barriers to collaboration - in our definition. Email so nicely compartmentalizes exchanges, with the power of inclusion and exclusion, the politically charged order of addressees and cc's, and the real sting in the devil's tail, the blind copy. Email also fosters the ridiculous proliferation of documents through attachments, making a complete mess of versioning and any reasonable control. Email is a barrier, a cage, a hole to hide in, a place to plot in and a weapon to wield, all over and above its clearly valuable uses and the positive-transformative effect it's had on our lives. Unfortunately it has over-stepped its usefulness into double-edged sword territory, and behaviours need to be changed for it to support real collaboration, and that means NOT using for many of it's current purposes.

B. Poorly configured Office Space is a collaborative killer, whether rooms or cubicles are overly compartmentalized (rabbit-warren style) or so open and uncontrolled that all privacy and the right to think quietly are destroyed. This is not the place for an architectural treatise, but there are good solutions out there, and organizations would be well advised to examine this issue closely. See for example http://myturnstone.com/blog/21-inspirational-collaborative-workspaces/ and the link therein, http://myturnstone.com/blog/office-zones/.

C. Culture is so difficult to define and to change, yet so essential to understand and to tackle. Like people, organizations develop habits, good and bad, and for their own health and well-being, the bad habits need to be turned around. Parts of our framework address this (incentive, leadership..) but it's worth being aware of culture as a single and large piece of the puzzle. It’s also a large enough subject in and of itself for another post!

4. Degrees of Social

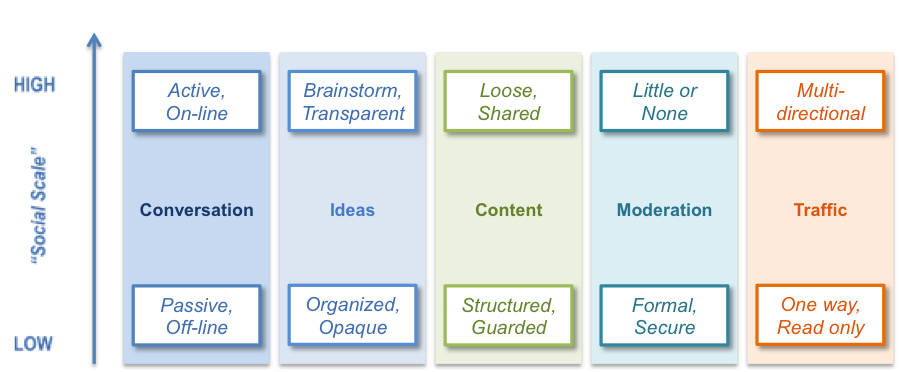

In the Facebook age, we tend to think of collaboration in Facebook terms. So let's return to "Facebook for companies" as promised. Firstly we need to recognize that different kinds of collaboration require different levels of sociability to be effective. For example, great collaborative work has been done by scientists across continents exchanging handwritten, sail-ship-carried letters. Was that efficient? Maybe not, but was it any less effective? No, it was arguably just as effective or even more so, as it allowed for pause and reflection in between communications - something we do so rarely now. Anyway, the point is that social can be good, but needs to be applied in line with the objectives. Consider the five elements in this diagram (yes the elements are pretty random, but hopefully no less illustrative)

A high-social environment is like a party: conversations are active, traffic is all over the place, nothing is moderated or structured, and most everything is transparent, music volume permitting. A low-social environment is like our inter-continental scientists, but imagine them being careful about how much and what they share. The question is this: according to our definition of collaboration, how social do we need to be? Of course there is a time and a place for everything (every party eventually winds down and we have to sleep) but we found that one of our major issues was that we were not social enough, and were stuck on the lower end of this scale. Even the tools I mentioned above (IM and the like) were under-used because they were too disconnected, and didn't "get the party going". With obvious pieces of the analogy aside, a good party is like good collaboration in that it needs leadership to happen in the first place, has energy and enthusiasm, helps form new relationships, and can be a lot of fun! The difference of course is in the outcome - we want a good product, a result we can be proud of, and not a hangover.

Can Enterprise-Social tools help here? Can they make the truly collaborative conversations and interactions happen? Yes they can, but they will also fail without the right culture and without ticking all the boxes we've mentioned above. Correctly implemented, they can support our objectives, and, for example, get colleagues to know more about each other, and to "meet" and work with colleagues that they might not otherwise have known about. But they remain a tool amongst others, and not a single means to an end, and it’s with that in mind that we’ve taken the leap with one in particular – which one is not important, it just has be the right one for the context.

5. Quick A-B-C-D

We’re still in the early days and I’ll publish more later about the longer-term results. But in the meantime this is how I suggest you proceed if you are contemplating a similar adventure:

A. Get your ducks in a row. The ducks are described in some detail above.

B. Don't jump into tools for their own sake – work out what degree of social is appropriate first, and what functions you really need the most. Treat it like any other well-run software selection, but put that social element high on the list.

C. Find enthusiastic pilot communities to get things going; learn from their lessons and adjust as you go. Also, consider letting the first pilot run the tool selection, and be prepared to switch tools if the one you choose isn’t absolutely great, especially in the early phases. Treat the early days as a “collaboration lab”.

D. Lead, lead, lead. Get the seniors on board and offering incentives and showing the way, while you enable the natural leaders at all levels.

I hope this helps the many CIOs and others who I know are being asked to tackle the collaboration question, and who are under pressure to implement something, anything, which makes the organization more “social”. Unless you understand exactly what kind of social is going to do it for your organization, social will remain a buzzword, and likely become a bad memory too. Please beware of the software vendors (as usual) who promise that their solutions will have you all collaborating in no time, regardless of other factors. It just isn’t true.

Two footnotes for enthusiasts:

1. The way we learn is changing

Let’s remember again that information transfer and sharing can indeed be done off-line, and formally (“low-socially”), but the issue is that behavioural evolution in our societies means that we take much less time and care to sit down and read or write. Therefore the more interactive and social learning and knowledge transfer paths are gaining importance, and in general people will learn more in an interactive session than alone. When you think about it, that's not really new: it's why we go to school as opposed to sitting at home reading books! But classrooms too are evolving, and on-line experiences are now part of them, and the best schools are evolving away from a lecture format into a round-table "learn from each other while you discuss" style. See for example http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harkness_table. (One of our self-imposed challenges was to create a Harkness-like environment, both on-line and in person.) If the goal of collaboration is to promote information sharing and the institutionalization of knowledge, we have to look carefully at learning and information transfer mechanisms as processes.

2. Knowledge transfer and repositories: man vs machine

This study led us to believe that “knowledge-bases” and “institutionalized knowledge” live primarily within the employees of an organization and not in databases. Computer programs, document and audio/video repositories, wikis and yes, collaboration tools, are all helpful pieces of the support structure. But in the end, the most meaningful transfer of knowledge happens not in writing/reading or recording/listening, but in the interactive telling of and participation in stories and experiences one person to another. Leveraging this reality in the pursuit of collaboration (and our defined benefits) means supplying a “high-social” experience, and that's part of what our solution aims to deliver.

* For “organization” please always read “company or organization”